When my mother was in her late forties, she sat down with a pad of lined paper and began to write. I had a second year university assignment I was working on from a class called The Sociology of Work. One of the tasks was to interview the working women of my extended family. So her writing was not a memoir exactly. It began as memories of her working life. Her words move between detail and distance, often plainspoken, sometimes poetic without trying to be.

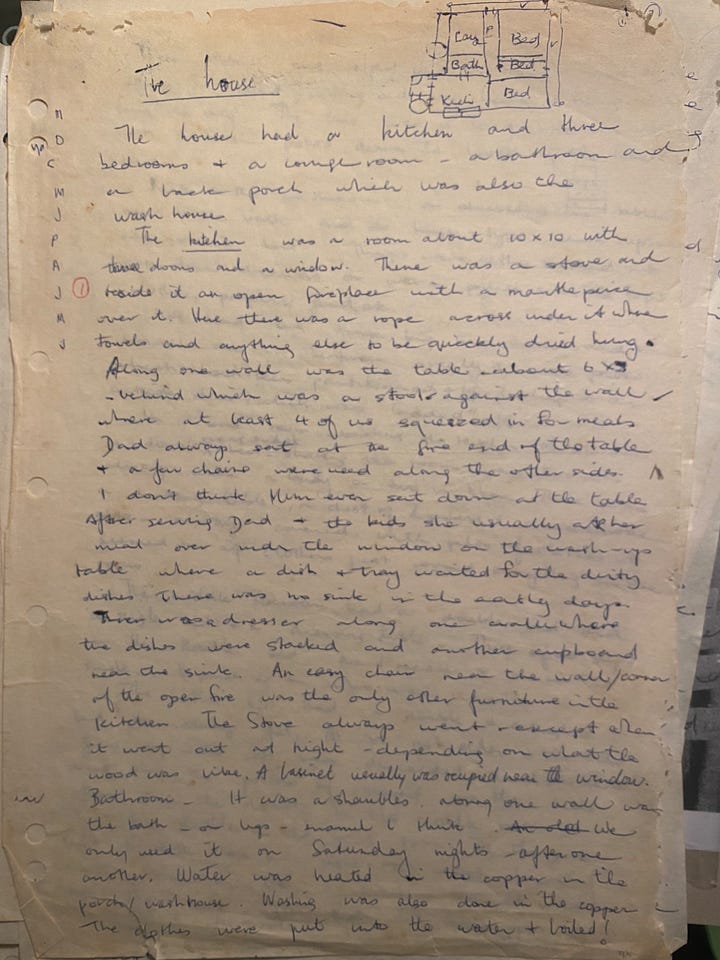

She described each room of the house she grew up in, the way roast potatoes crisped in the oven, and how it felt to slip away and sit quietly, drawing in the gravel by the roadside. Her handwriting has become something sacred to me. It carries rhythm. Hesitation. Emphasis. Care.

This poem was shaped by her voice. I’ve included her words and handwriting here, side by side with the finished piece.

Life Lines My Father always sat at the fire end of the table— dry hands, life-lined, and waiting. A bench ran along the back wall, a few chairs lined the other side. I don’t think Mum ever sat down. After serving Dad and the kids, she ate her meal under the window— at the wash-up table where a dish and tray were always waiting for dirty plates. There was no sink in the early days. A dresser ran along one wall where clean dishes were later stacked— ready, and waiting. The only other furniture was an easy chair in the corner by the open fire always ready for a visitor. I always stayed away a long time when a roast was cooking. Roasts were best if I came home late— my plate set aside and slid into the oven. Everything would crisp— the meat, the potatoes— a wonderful brown coating sealed in by my mother’s waiting. I always stayed away a long time when a roast was cooking. It was not much fun to be at home— just something else to do: wood to chop, clothes to hang, potatoes to bag, a muddy floor to wash. It was good to just sit against a warm stone wall somewhere, and dream. Or draw in an old exercise book, or scratch patterns in the gravel by the side of the road with my stick. The cows often wandered off when I was minding them. I’d hear the horn of a car— a cow on the road, a car, waiting. Time to get up, and run barefoot to bring them back to where they belonged. To the paddock. To where I'd leave them waiting until milking time when they'd be ready for our call and the life lines of our gentle hands.

“ The kitchen was a room about 10 feet by 10 feet with three doors and a window. There was a stove and beside it an open fireplace with a mantlepiece over it. Here there was a rope across under it where towels and anything else to be quickly dried hung. Along one wall was the table about 6 feet by 3 feet, behind which was a stool against the wall where at least four of us squeezed in for meals. Dad always sat at the fire end of the table and a few chairs were used along the other side of table. I don’t think Mum ever sat down at the table. After serving Dad and the kids she usually ate her meal over under the window on the washing-up table where a dish and tray waited for dirty dishes. There was no sink in the early days. There was a dresser along the wall where the dishes were stacked and another cupboard near the sink. An easy chair near the wall, in the corner by the open fire was the only other furniture in the kitchen. The stove always went, except it went out at night - depending on what the wood was like. A bassinet usually was occupied near the window. “

“ I don’t know what we lived on. Money was not seen. Dad signed a cheque for Mum once a week and she would catch the bus (from Geelong) to Ballarat to shop. Sometimes he did not make it back from feeding the cows in time to sign it and Mum would catch the bus with very little in her purse. We seemed to live on potatoes and lamb / mutton. When the meat ran out we’d kill another weather. Dad would bring one home in the cart. Cut its throat and hang it up in the big Lucerne tree out in the back yard and we’d watch dad cut it down the belly and clean it out. I always marvelled at how the inside would steam. He would skin it then and dry the skin out on the barbed wire fence. (The skins were sold when he had collected enough). Then a sheet was then thrown up over the hung sheep, and it was left until morning and then the sheet was sewn into a bag and put away.”

“ Roasts were great especially if you left getting home for lunch really late and it was put in the oven for you and everything was crisp on the plate - with a brown coating on all the potatoes and meat. I always stayed away a long time lots of times as it was not much fun to be at home - just something else to do - wood to cut, clothes to hang out, potatoes to pick into big bags or a floor to wash. It was good to sit against a stone wall somewhere and dream or draw in an old exercise book with an old grey-lead or draw patterns on the gravel by the side of the roads. The cows often got a long way away when I was minding them. I’d suddenly hear a car horn which meant a cow was wondering over the road. Time to get up and race up in my bare feet and herd them together and put them in the paddock. ”

These are only fragments, there is so much more. But through them and as I take the care to write a poem in here voice, I hear her more clearly now and I understand a bit more about my grandmother and grandfather too. Not just what she said, but what she never said. That’s the beauty of handwriting. It holds memory in more than words.

I’m grateful to be able walk alongside her, for a little while and keep an eye on the cows while she daydreams.

Great work Damien,keep it going!

Beautiful words

Dear Peggy 😊