Go Dance with Her

(for my great-grandfather, miner and lover of Saturday nights) The fiddler is late for the dance— lost in the dark somewhere on the road, moonlight not enough. You wait with the other men in the shy shadow by the gate. There’s a storm far away. Listen to its deep music and a familiar woman’s laugh coming from under the lamplight— where the sound of hard heels on sawdust and floorboards calls you. She is there, your Annie— a breath of fresh air. Go dance with her. Let your courage wash the doubt dust off. Get out of your cage. Don’t be dynamite deaf, reluctant alchemist— it’s a new century now. Find your metal. Release the pressure valve. Stoke your boiler heart. Tumble toward your love in the dancehall of delights— Saturday night. Let night air break your fall. Step into the bold lamplight. Leave the clearing steam of the high shed behind tomorrow's sunlight will grow gold. Let your mercury run back to the bottle. Listen— the mines are silent now in your ringing ears. The cages are lifted for the last time. The windlass has stopped. The boiler has returned to the road. The fiddler has found his way to this Saturday night. Go dance with her.

After working a long shift down a mine, it must have felt good to be lifted in that cage for the final time and dust off, get dressed to the nines, and head to a dance. Most young men in those days rode bicycles, sometimes for miles, just for the chance to dance with a woman they liked. Looking back, it was how many Australians socialised and courted one another.

The small country towns south of Ballarat had a vibrant Saturday night dance circuit from the 1860s right through to the early 1970s. When I was a child in the late 1970s, I’d sometimes go to a local “Old Time Dance,” though by then it was mostly attended by older people and children. Most young adults had shifted to pubs and nightclubs to meet each other.

Old Time Dances had strict rules about drinking. It was frowned upon, and if you were drinking, it had to be at least a hundred yards from the hall. So, if the young men needed a nip of courage, they’d be out in the shadows, out of sight.

Most of my ancestors in this part of the world, from the 1860s onward, were of Irish descent and Catholic. My great-grandfather Maurice certainly was. The Annie (Anastasia) in the poem was a little different: her father had come from Norway, but he married an Irish woman.

In studying my ancestors from this time, I noticed something: they either came from large families, nine or ten children, or they ended being bachelor uncles and spinster aunts who never married.

One of those bachelor uncles, Martyn Hansen, was a fiddler and piano player. He was famous for riding his bicycle across the district, from Enfield to Creswick, to play at dances. He did this right into the 1950s. He was paid ten shillings to play and would tell how sometimes he’d arrive late, especially if the roads were flooded, and occasionally he’d still be riding home as the sun came up.

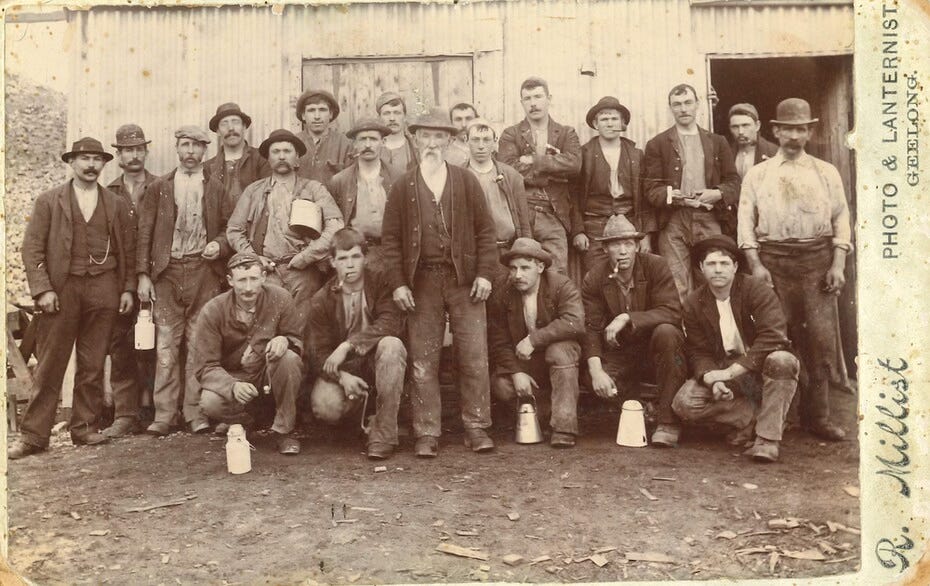

Maurice, my great-grandfather, would have known many of the men in the photograph below. He lived in Berringa but worked down a mine in Dereel. The men in the photo worked a mine in Rokewood, about 15 miles away.

Mines then were big industrial affairs. Most of the machinery was steam-driven. A great iron boiler at the heart of the mine powered the winding gear and the cage that brought both men and ore up from below. Many of the men in my extended family back then, if they weren’t underground, were employed supplying vast quantities of timber to keep the boilers and engines going.

So as far as the mine as metaphor goes in the poem above, this time it lifts the poem toward where I am this Saturday night.

I’m not sure where it will lead me next.

Probably down into the dark.

Hi Damian

This is a lovely evocation of a not so different past.

I grew up in underground coal mining country - the lower Hunter Valley - where the poppet heads that once dotted the landscape in my childhood are now all gone, or preserved as an historical oddity, and the annual miner's picnics are now a memory. Those memories of mine - and I suppose of yours - are echoes of your Great Grandfather's earlier time, which comes to life in your poem.

Best Wishes - Dave

So interesting Damian...a different time and yet your note tells me how the mine and the last rising of the cages is indeed a metaphor for the present...wonderfully woven.