In my recent posts, I wrote about my great-grandparents and life in the mining towns near Ballarat in Australia, where my grandmother grew up. I explored the effects of gold mining, hard work, and family silence. Now, I’m moving forward, to the world my mother, Peggy, knew as a child.

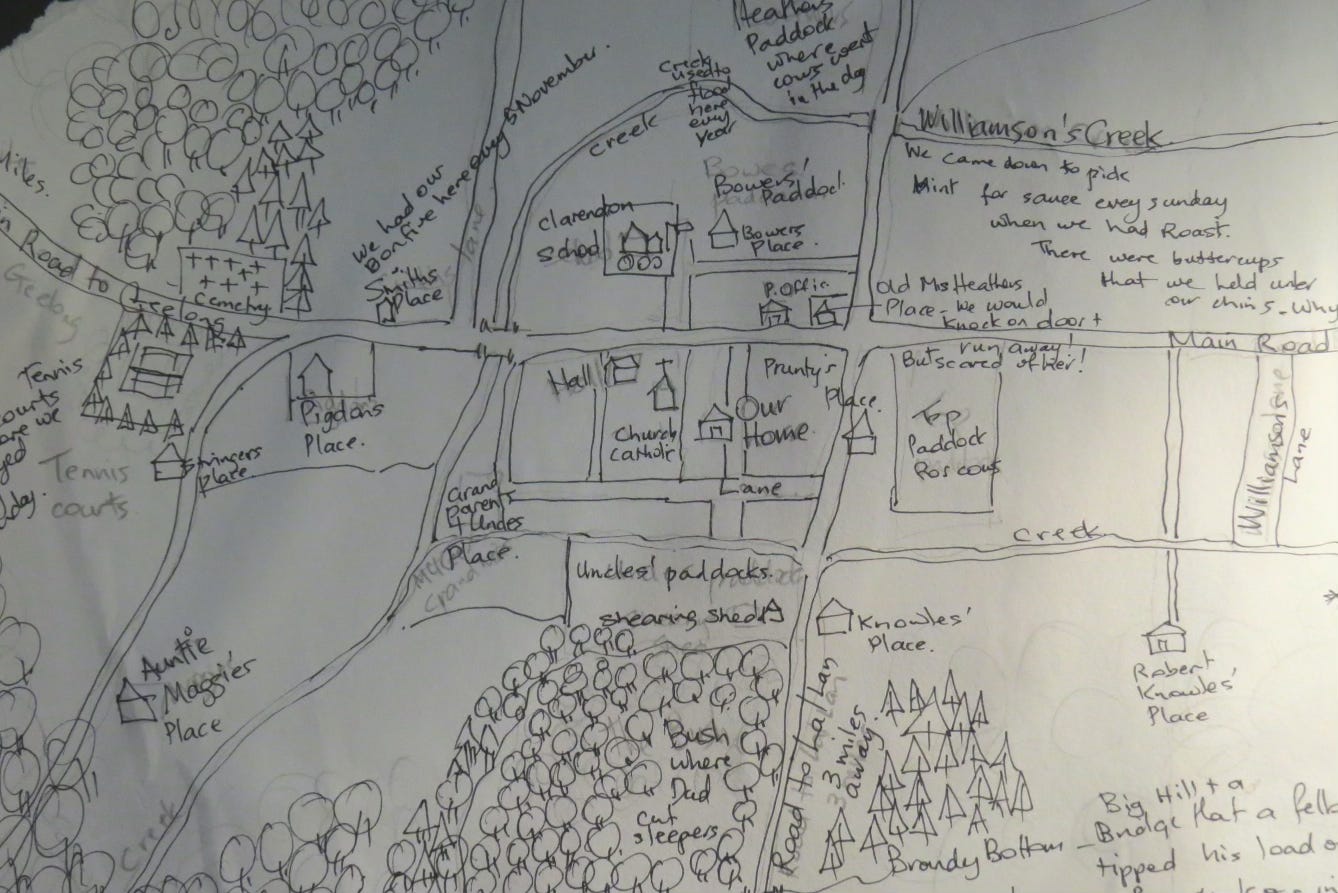

After marrying a farmer named Jim, my grandmother Molly moved out to a small community called Clarendon. Jim was ten or more years older than Molly. He owned a small farm among other land owned by his relatives. Together, they raised ten children. My mother was the sixth child.

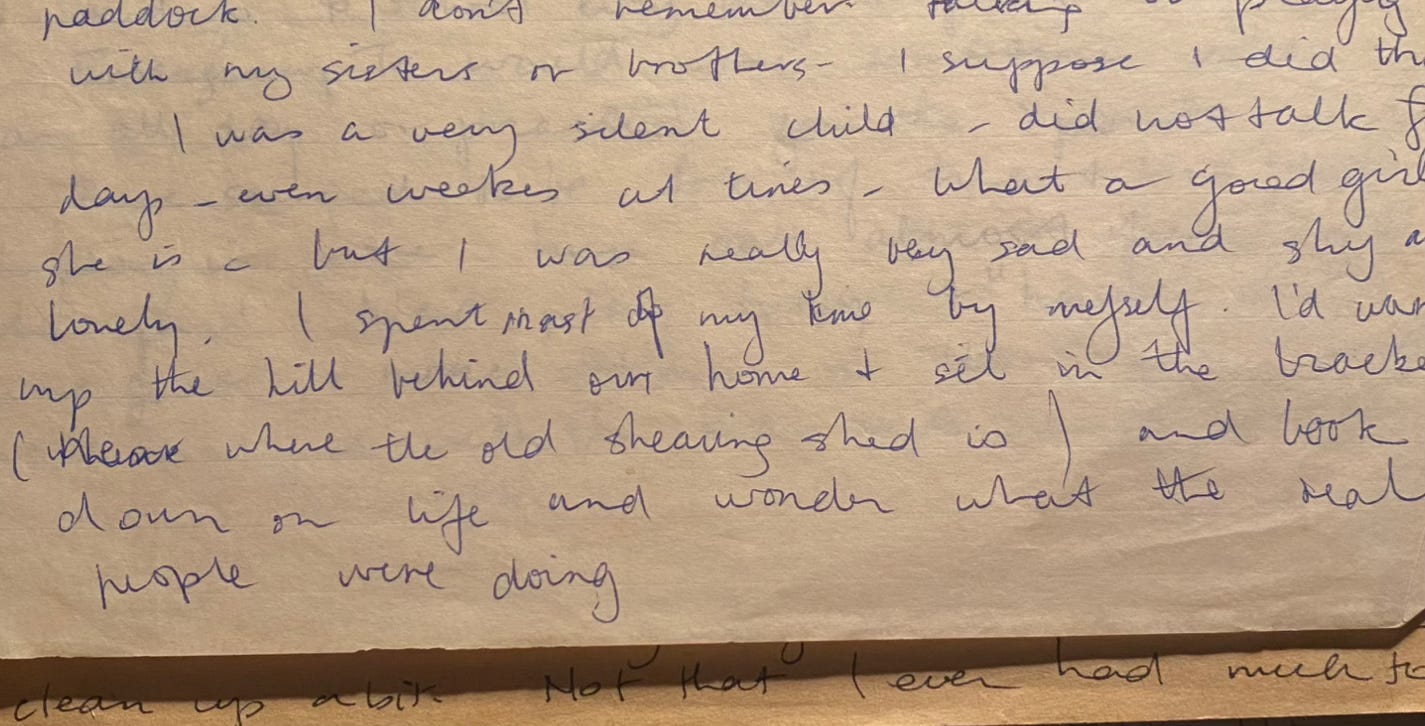

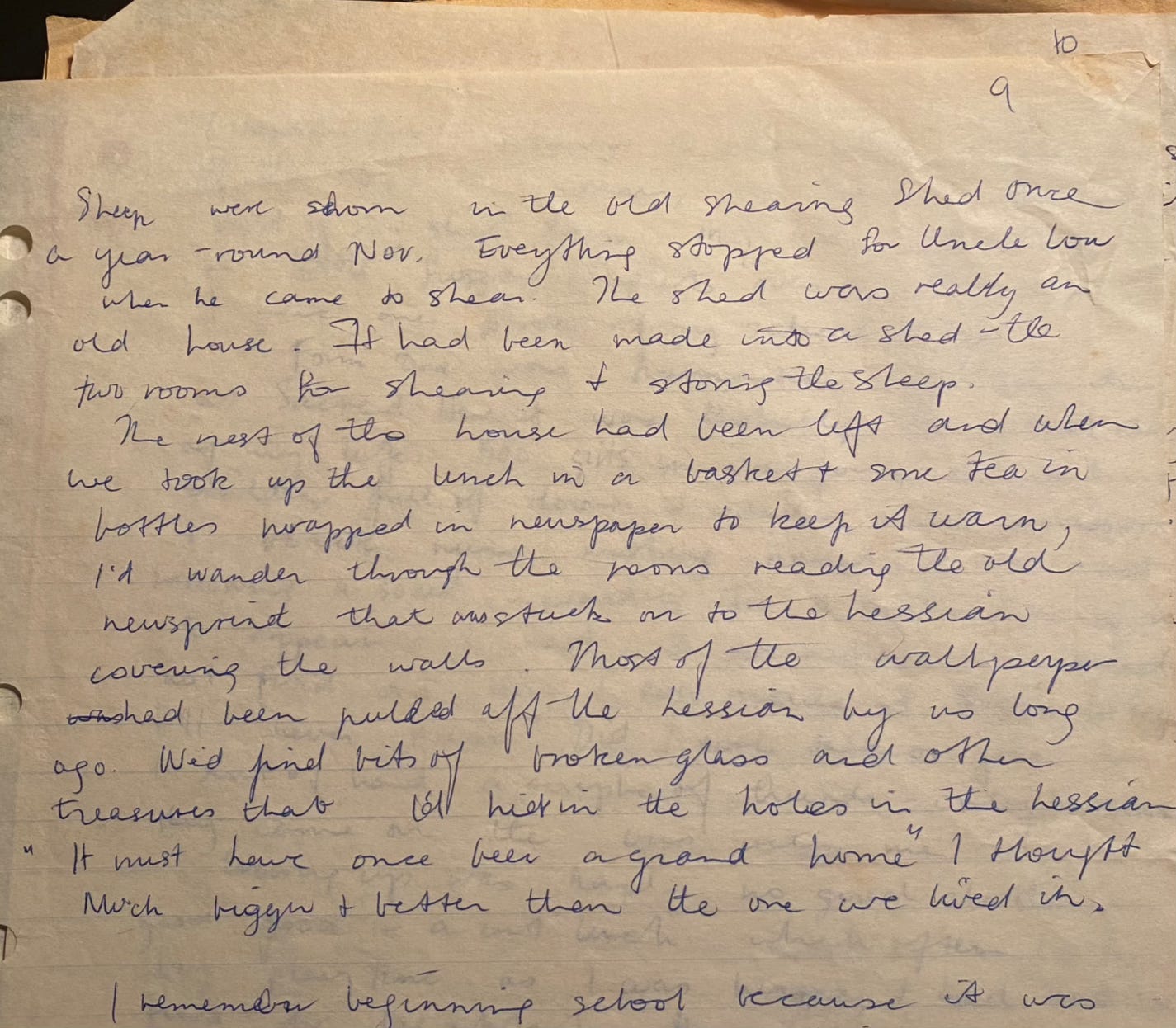

We first glimpsed the imaginative world of my mother’s childhood in my earlier post & poem Tickling Eels in the Creek. This new poem, A Shawl of Bracken, is drawn from one of the hand-written pages she left behind in a short memoir. In it, she describes being a silent, watchful child, she also writes about an old house in the back paddocks, that her father and uncle had converted into a shearing shed.

My mother wrote about twenty pages in total, on foolscap paper. Recounting her early life: the poverty, the rooms of her family home, how each space was used and remembered. Reading her words, I begin to understand how ordinary objects and places took on quiet significance. I get a sense of where her thoughts wandered when she was older. Where her inner life took shape.

This poem is the first in a small series where I will draw on those pages. Her words guide me in my poetry. They shine like scattered glass in the paddock dirt. So I will take the words that strike me the the most an maybe craft a poem with them.

In this piece, I follow her memory of being a silent child, and my own fascination with the old house on the hill, that in her words, was once grand, but falling into ruin. I visited the shed / house myself years ago, before it finally collapsed and disappeared, at least physically. In the photo of my mother (below), you can just make out the old house frame and chimney on the hill behind her.

This is where I begin.

My mother, Peggy (above photograph), with the old shearing shed / house of the below poem just visible on the hill behind where she used to “sit in the bracken”. Mum was very sick with cancer in this picture and this was her last visit to the back lane of her childhood.

A Shawl of Bracken (for my mother, Peggy) I was a silent child, wordless for days— sometimes weeks. “What a good girl she is,” they’d say, not seeing the quiet as loneliness. I wandered alone up behind our house to where the old shearing shed rattled in the wind on the southern hill wrapped in a bracken shawl. Once, it had been a home— grand, bigger than ours. You could still hear voices sometimes low in the wind moving through the back rooms like an old woman finally home with firewood. Our sheep were shorn there once a year— when everything stopped for Uncle Lou. We’d take up lunch in a basket, tea in old bottles wrapped in yesterday’s news to keep it warm. I’d slip away from the newly shorn ewes, wander the empty rooms where wallpaper once hung— glued to newsprint from 1916— to hessian walls that shifted in the drafts. We’d pulled the pattern off years before but I’d still read the advertisements for Ford cars and .22 Remington rifles. I found treasures too: dark green glass, brass buttons hiding under rusted tin. I’d tuck them in the hollow walls for safekeeping. Then I’d look down to the highway, and wonder what the real people were doing. Not knowing I was real too. I just hadn’t spoken my mind yet.

The above map shows the visual geography of my mother’s memory. It’s part treasure map, part memoir, part oral history.

Companion Piece: Tickling Eels in the Creek

This earlier poem was one of the first I wrote from my mother’s childhood memories.

It captures another side of her childhood. Not the loneliness of being unheard, but the wild, wordless joy of being in the creek at night, with her hands in the mud and a brother at her side.

Tickling Eels in the Creek.

You laughed

as I lifted up the dark, beautiful thing

and threw it on the bank.

Bewitched as it danced,

too slow to jump on it or hug it,

it escaped through the tangle—

that beautiful black eel in the night,

alive under moon and stars.

We settled back down,

chins on the crumbling edge,

arms in the water,

hands in the mud,

waiting for the moment,

waiting a million years,

in a child's mind.

You sighed,

“we’ll be here all night.”

“be patient,” I said.

The rabbits rustled,

the fox listened,

the stars shimmered,

our faces—dark faerie reflections.

Our father could be heard, coming down the hill,

a ghost from Loch Neagh

to call us in.

But we were lost in the night,

tickling eels in the creek,

knowing nothing of what the old ones knew.

“Call us in.”There’s something sacred about returning to the places our mothers wandered as children. Especially when those places no longer fully exist. A crumbling shed, a hill covered in bracken, long since cleared. The memory of warm tea in bottles wrapped in newspaper. These aren’t just details, they’re doorways. Through my mother’s handwriting, her drawings, her stories, I’ve been allowed to enter that world as a poet. To sit beside her again, not just as a son, but as a listener from another time. A quiet witness. These poems are my way of saying: I see it now. I see her now. And in the creek, in the hill, in the windswept grass of those paddocks, I’m beginning to hear what she never got the chance to say aloud.

What a beautiful, melancholic journey, an homage to your mother.

This chimed A LOT. I am writing about my own mother at the moment but, in the silence, struggle to find her voice. Very moved by this, Damian. This might well move me on. Thanks.